Antinomicity

。°。

Antinomicity 。°。

Antinomicity - Novella

What begins as a description of a father walking with his son through Newcastle, Australia, becomes a meditation on landscape, subjectivity, music and the counterpoint of solitude and community. A philosophical work of psychogeography, this novella by educator Craig Warren Smith explores the scale at which memory takes form.

For Nietzsche, midday is not a moment of unification, when the sun embraces everything, but is, instead, presented as the moment when 'One turns to Two'.

— Alenka Zupančič

The light is like a kind of lengthy explanation - the light is like two thoughts occurring at once.

— Matthew Welton

*

Preface

I once overheard advice that to be a good poet you should spend years walking on uneven ground. Abrasions in the landscape, sloping declivities, meadows that turn into boulders – these are where one develops an ear for a line of text. A lifetime on concrete can only provide the most pedestrian of rhythms, too regular, like a metronome conducting a marching band. Given, then, that most of this book was written along level, constructed, synthetic trajectories, I could use this to justify prosodic weakness and flatline cadence, with the exception perhaps for one patch of treacherous ground that was the birth knell of this book.

There is a secluded beach in Newcastle that is only accessible at two entry points – the easiest way, but less reliable, is to curve around a narrow run of sand that links to an adjoining beach, but this is only available during a significantly low tide, and it feels as though this is occurring with diminishing frequency. The most reliable, but more fraught, access is to hop over a safety fence at the top of the cliff that shadows the beach, carefully making your way down an improvised walkway of flaking shale and loose stones.

I’m setting up the punchline here by foreshadowing the situation, as this is the path I took one late afternoon that saw me, seconds later, lose grip and dance atop a crescendo of rocks that rapidly became impatient with my stability, leading me to tumble, somersault, down the cliff for some handful of unforgiving seconds until I thudded onto the sand.

While I sat in a nearby rockpool and bathed my wounds in salt water for the rest of the afternoon, my mind settled into its favourite posture, one of earnest reverie, cycling through recent and distant memories. It feels as though my reflections naturally slot and sequence within two broad categories - time spent with, and without, people. Mostly, I thought about a recent period with my children, and the sort of mirror they bracket around my waking life. A succession of events that occurred across no more than a week became the narrative of this short book, and in reading back what I have written it feels as though a very particular moment, developmentally, in the lives of my children, my wife and I, has, through the following thirty thousand words, been cast in an epoxy resin time capsule, like a family of insects preserved in amber. My son, for example, is different now in his language and his interests, just a few weeks on from when I finished writing this book, and yet I can witness with paternal tempo the way he was during the period described, through the eyes I was using at the time.

Dangling my bruised legs in the water, allowing the ocean waves to cleanse them, and hoping that I hadn't suffered any long-term injuries, I thought too about the role that walking has on my life. If my memories are separated into occasions with and without people, then my daydreams are nearly exclusively focused on places I can walk to. Psychogeography is what propels me forward, in both the physical and the metaphysical sense. One conclusion that I come to early on in this book is that walking in a conscious manner, with a view to observation, feels like a hunt for external landscapes that analogously mirror the internal landscape of subjectivity. If this book contains a detectable pulse, this idea might be the pump that regulates the flow.

How many ways are there, these days, to walk without walking, beyond prose. My daughter and I found a virtual reality program called Japaneland that allows you to float above the islands of Japan until you see somewhere you'd like to touch down, at which point you drop into a region that has been graphically rendered based on satellite mapping data. Then you get to, quote unquote, walk around the neighbourhood. It's like taking a stroll through a computer-generated version of Google Street View, glazed with an algorithmic filter that make brick walls look as though they are made from caramel gelato.

Too, the internet today houses hundreds of thousands of walking videos, where somebody with a camera strapped to their chest moves about an English country lane or a Korean midnight metropolis, giving a first-person view of what it looks like to footfall those avenues. I have seen a video where somebody walks the same path that Friedrich Nietzsche used to hike when he moved to the coastal town of Èze on the French Riviera. You see, in a way, a version of what Nietzsche might have seen, with whatever changes to the flora that a hundred and forty years have had on the landscape there. Of course, we can't really see what Nietzsche saw on his walks, because our inner world is not the same as his, but it’s a nice idea.

What sort of poetry will this ambient psychogeography bring about, of a new generation walking through virtual landscapes, where the ground is not uneven or level, but groundless. How will the pace of our phrasing be altered, has already been altered, and what will it do to memory and daydreaming. Already it provides a way to displace, to speculate on, our position in time, kneeling down in Kotohira and admiring a garden bed hologram of chrysanthemum that resets and loops every few minutes, forever now, for a while. What I hope is that the impact on us is completely unexpected and, more than this, feels utterly wrong. Art that works is art that fails, because intentions are arrows that hit when they miss. It is the accidents that resonate with us because the human element is subtracted - the revelation is in the breach.

In kinship with this consideration, this invitation for error, in parenting and in time, holding a hand younger than mine, with best foot forward, I begin.

*

Chapter 1

The thing I like most about quiet, open, brutalist spaces like this, the TAFE here, exploring it with my son on a Saturday morning, his two-year-old little mind and body spontaneously engaging with the concrete stairs and ramps and sudden brick facades in a manner that gives language now to what I most like about being here, is that spaces like this seem more like a playground than a purpose-built playground.

They proffer genuine exploration in the root sense of the word, originally a hunter's term - to release a loud cry - from the Latin ex 'out' and from plorare 'to weep, cry', scouting an area by shouting aloud. But also how we get plorare from pluere as in 'to flow', which is what my son and I are doing here, walking across a slight brick elevation where two flagless poles are planted, onto a concrete walkway that curves between two sheer brick walls that rise from the mushrooms at their feet to the thin cloud streaks at their apogee, everything here made from either brick or concrete, until we find our way to the back of a building that seems to host education in metal forging.

There are metal tables, metal tubs filled with dozens of offcuts of solid metal cylinders and something the shape of a road bump, or perhaps not a road bump so much as a mantle clock, raised supports for the metal cylinders that my son and I roll along the ground and into puddles left by an overnight storm. This is how we play, how we flow, and while we don’t cry aloud as we scout the area, preferring instead to talk gently to each other, there is something to this etymology of the word explore that speaks to me - to weep, cry - not out of any sort of explicit sadness, but of a melancholy that takes residence with empathy, the way that memory is a bittersweet device, treating you to a remembrance of things past while reminding you that this is also where they live now, in an ever-fading capacity.

This is why I take so many photos when my son and I explore together, as many photos of him in the environment as the environment itself, but never of me, not a fan of the selfie. I try to capture a view of what I see when I feel grateful for consciousness, when I recognise how much this particular moment in time fits me like a glove. Watching my son roll metal cylinders across a bitumen embankment into puddles filled with clouds, this is the shape of my mind cupping its hemisphere-like-hands together as empathy is poured in. And, because our hands are poor vessels for holding liquid it flows out between the crevices, hence why I take so many photos, to hold time in a state of suspended animation before the moment passes.

It feels to me that photography was not an accident but rather a decision made long ago within the structure of our brain. One-and-a-half million years ago when our brains developed a frontal lobe we learned how to reflect on our reality. The frontal lobe created a buffer between mind and matter, a delay between our unfiltered contact with the real and the way we subjectively process it through replay, our entire conscious experience of the world simply a reproduction of what has just occurred out there, earlier, in the unprocessed world beyond the language of our awareness. How could we not create photography to simulate this, just as we created dance, art, music and narrative before it, to synthesise this feeling. The brain said I am a replay machine, so let us create another machine that can replay the replay, over and over again, to duplicate the duplicates, and it was done.

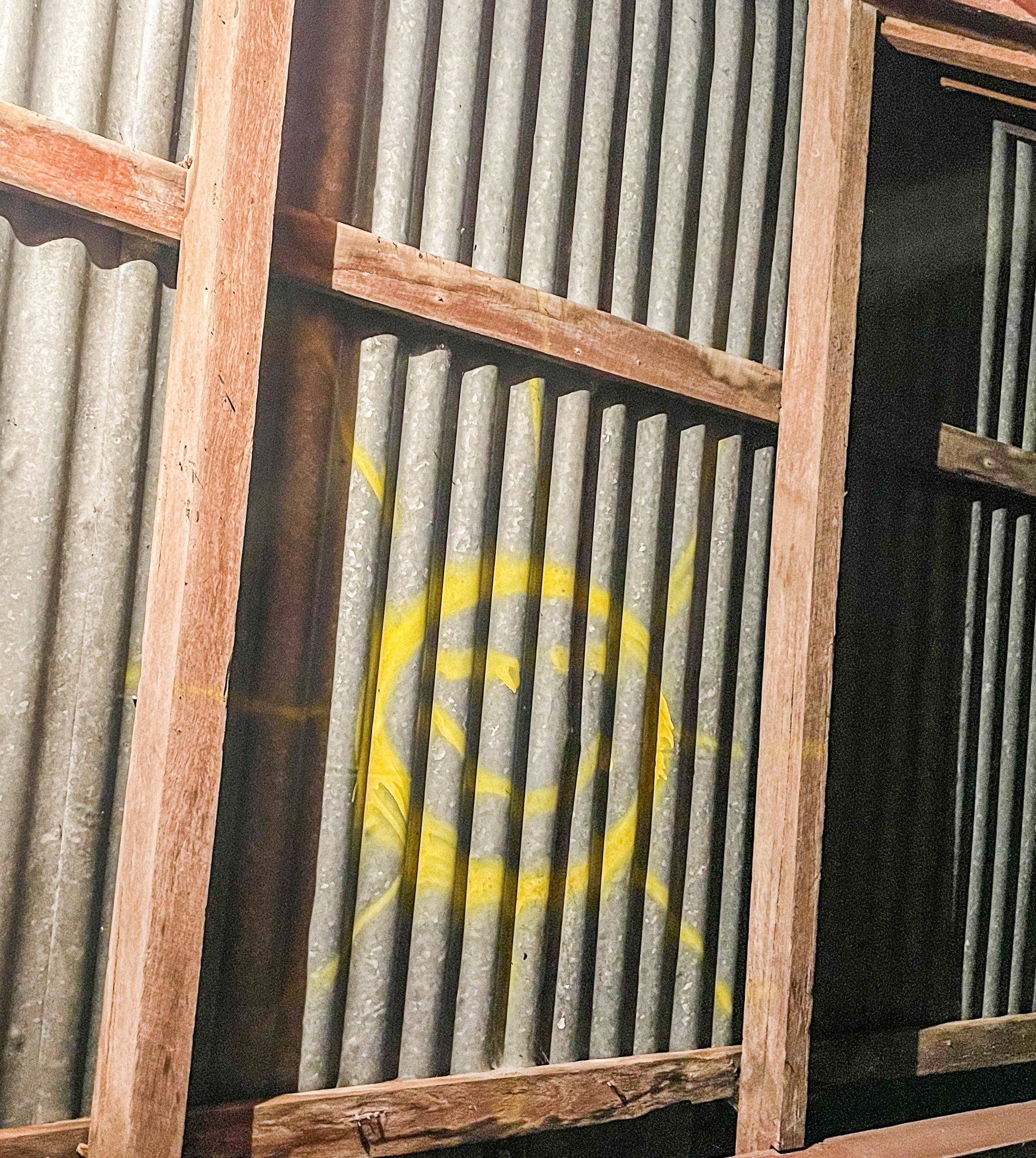

When I take a quick glance through the photos geotagged to the location of the TAFE, I see six hundred and fifty-five results that fall into the following categories: photos of my son riding around the empty car parks (we only ever go when the campus is closed, like on a Sunday morning or public holidays); photos of my dog careening around the footpaths; photos of the grass strip that divides one side of the campus from a creek beside it, a creek birthed by way of a metal filter that halts the flow of detritus from the drain that precedes it some twenty metres to the south east, the grass strip containing a wooden bench seat and tables that we, my son and I, sometimes take a break on; photos of the train line on the other side of the campus taking coal carriages back and forth from the loader at the port through here to the mines up north; photos of my son and occasionally my dog exploring the courtyards of buildings, spaces of infinite calm, tracts of concrete and grass necklaced by five-storey boxes of how many hundred thousand bricks (I think of those who spent months of their lives here placing one brick on top of another in such perfect sequence, a bricklayer who recently did some work for our family, brought out of retirement for one or two more jobs because, in his words, he is one of the few who still take pride in the job, who doesn’t drop tools and speed away when the clock stops and couldn’t care less what has been left behind, not that this is a comment on the current young cohort of builders, he says, it was the same in his day too, back in the seventies there were the ones who turned their back on a sloppy, unfinished job the moment they got a chance to hit the beach, not that he hasn’t occasionally done that himself or got himself in a bit of trouble over time, the time he walked off a site and went AWOL for a couple of days, drove down south to the snow to do some fishing in the lakes there, took how many cases of beer with him, fell asleep outside and would have frozen out there except for the immense need to urinate that woke him, and as he stood and relieved himself he looked up at the night sky and saw more stars in one place than he had ever seen in his life, and as intoxicated as he was he knew that those were a field of suns up there on some unintelligibly grand scale, and when he later returned home he felt an exhaustion in every part of his being like he’d never felt before which did not leave him for two years, so weary that he could not work for that whole time, so he took the phone off the hook and he and his wife survived on vegetables from their dusty little garden for twenty-four months before one day his energy returned, filling up his body again like an oven stoked with birch, and now here he is, still at it today, for one or two more jobs at the very least), and in the photographs of the courtyards I feel again the cool of the shadows, what I sometimes describe to myself as triangles of shade, always a relief across the Summer months when the TAFE is closed for nearly six straight weeks and we come here most mornings; photos of the grandstand that looks over the football oval where we climb up and down across the long timber benches, where I prompt my son to not climb on the corrugated roofing sheets that you can just walk straight out on from up here; and photos of the bridge that spans the creek in a midpoint between both sides of the campus, the fracture in the closed system that allows the outside world into this quiet synthetic urban bubble, although to be fair their is a three-metre tall gate on the bridge that is almost always locked, especially when we are here during public holidays and weekends, and although we respect the role of the gate, riding up to it and bumping against it, making the metal gate rattle against the metal railings of the bridge so that it reverberates against the buildings here like a dissonant gong, percussively celebrating its function, there are others in the area who walk up to the gate and vault over it in order to make their way from the suburb on one side of the TAFE through to the other, as it is by far the most direct path to cross the area rather than walking all the way around the neighbouring streets, waiting for the train gates, and so on. Unless you were to walk up the dry part of the creek-turned-drain, which I often do alongside my dog, without my son.

The point at which the riverrun creek transitions into a dry, walkable storm-water drain is located beneath a rail bridge that carries both freight and passenger trains (but not coal, which travels on the other side of the TAFE for a brief moment before diverting to the highfields). My dog is comfortable with the rumble now as the trains pass overhead as we trespass the drain’s broad, curved trajectories from one side of the city to the other. We don’t start here, though. Our walk commences two kilometres back, two of the over five hundred kilometres of drain network across the city, expanding and contracting to varying degrees of width. The stretch we walk spans twenty metres across, but it narrows to only three or four metres as it slinks into the heights of the suburbs. Aside from a couple of bridges the drain is completely open air, seated some three metres below ground level with steep concrete walls, appearing somewhat like a baking tray or a marble run.

I first guided my dog down here after reading a book by a local author about his own walks through the drain with his dog. The book was written in the style of the English naturalists, the walking phenomenologists who made it their mission and their pleasure to observe the area in which they lived in service of folk scientific inquiry, learning the names of the plants, the variety of birds flitting about, recognising seasonal patterns. There is a section in the book where the author wanders beneath a fold of torn metal fencing into the disused gasworks that runs alongside the storm-water drain, and he says that if asked by any remnant security or council workers why he was trespassing, he would simply say that his dog ran through the fence and that he was just going in to retrieve him. That was enough of a license for me to do the same.

Putting aside the joy of watching my dog run free through the length of drain as far as my vision carries, in which we have never in my years of doing this come across another dog down here, and only very occasionally another human traveller, my favourite part of the trek is a length of some five hundred metres that curves out of view from the nearest bridge or roadway, not visible from the rail line either, so that for some ten minutes of walking it is as if I am the only human on the planet. It is a solipsist’s dream - on one side is the abandoned gasworks, on the other an abandoned fuel depot, both vacant of any activity, and growing along the ridge of the walls of the drain are these immense golden willows that hang low their branches and rustle like a nineteen-fifties mesh coin purse that softly pleat coins of jangled sunlight. Sometimes I lean back and watch the trees repeat their breeze-jostled sequence for twenty minutes while my dog finds a warm patch of ground to embrace.

One early morning some weeks back, beneath just this sort of gentle acceleration of sunlight, my dog and I clambered up the concrete walls of the drain at a point where a minor stormwater course joins up with the central passage and found ourselves on a raised spit of field that backs onto the old gasworks. Not only backs onto but leads into, as a nearby security gate is wide open within the surrounding mesh fence line. Until the nineteen-eighties, the gasworks turned coal, through an oxidation process, into gas for the city. Now it sits vacant, a half dozen silos casting shadows over bullgrass and dust like a batch of giant, discarded sundials. Most of the stairwells attached to the side of the silos are wholly rusted away, but one remains intact, enough so that my dog and I can ascend to the top without any hassle.

On top of the silo I feel a sudden sensation to recline on its flat concrete lid and close my eyes, my dog already doing the same beside me, in a gesture that I can only describe as being analogously triggered by another mirrored circumstance some months prior. At that time I was, again, walking with my dog down the drain but in the opposite direction, towards an area surrounded by sporting facilities. It was coming into twilight, but the sun was in a similar position to now, just on the opposite side of the sky, falling instead of rising. My dog leapt up the sides of the drain to get to the grass up there, preferring its soft texture beneath his paws after all that concrete, and when I followed him up I saw we were on a bank of turf behind a fence at the back of a soccer field. Soccer season was over for the year and the grounds were empty and inactive, but just like the gasworks, a security gate within the mesh fence had been left open. So, we walked in.

The grass was dry and wispy. It looked like it had been some weeks since it was last mown, and perhaps this unkempt appraisal beckoned my dog to freely bound around its quadrant. The soccer field is at the back of another sporting field, which is at the back of a tennis facility, so it is out of view of public thoroughfare when not in use. This is not an excuse to just let a dog run around a private sporting facility, nor an excuse to wander into an abandoned gasworks, but sometimes moral problems give way to aesthetic solutions, especially when ambient evening light presses its weight over an expanse such as this. It had been a long day and a long month, and as I wandered onto the middle of the pitch, I sat down, looked up at the extinguished stadium lights, and thought about how peaceful it would be to fall back into the grass and go to sleep there. I woke up some two hours later in the dark, with a back pocket full of missed calls from my wife.

Forty or so minutes (who is counting) after deciding to recline on the top of the old silo, I opened my eyes and realised that the same thing had happened again, just as on the soccer field - I thought it would be nice to have a rest in an empty public space and unknowingly, without anticipation, fall asleep, but who would have thought I would see it through. I woke up facing the sky with a start and gripped the roof of the silo with clamped fingers, worried I was nearer the edge than I actually was. Slowly turning my head to the side, I locked eyes with my dog as he began reading my expression, which I immediately softened so as to not cause him any undue distress. Beyond his curled form, big brown bucket of fluff that he is, I looked across the pitched rooftops of nearby factories and warehouses, across the rail line, to the TAFE where I could see the quarters my son and I covered there, from the creek to the car park, from one magnitude of bricks to another to the courtyards in their wake.

Gazing across a broad expanse of geography fills me with a sense of pending internal completeness. When you sit on the beach and look out to the ocean or sit on a porch and look across a field towards a distant mountain range - is the attraction a physical one, a resonance with symmetry, scale and colour, the lines of the environment, an impetus to action. Or rather, is it a metaphysical attraction, rendering the ocean and the field as metaphors, as an architecture of poetics that conjure feelings of freedom, infinity, the purity of faultless nature, and our kinship by association.

I have come to think of my relationship with landscape as one of subphysicality, beneath conscious association and physical connection, within enclaves of unintelligibility in a manner that positions these landscapes as analogous to the shape of the inland empire that is my subjectivity. These landscapes are not analogous in an abstract form within my mind; instead, they exist as my mind - subject as object. To look from the ceiling of the gas silo across an expanse of grassland and industry is to recognise the literal chemical, electrical silhouette of my own awareness. Environmental declivities and ascensions are carved into the fabric of my consciousness as into an inverted mirror, allowing landscape to pour into the negative space at the foothold of my thoughts, providing to the body a simulation of what division without remainder might feel like.

During a recent afternoon at the TAFE, while my son and I were going up and down a stairwell that leads to a storage corridor beneath one of the buildings, I spotted a lady, in her sixties say, five foot-something, wiry and postured forthright, dressed in dark materials with patches of purple and green that I associate with tapestry, and what I saw her do was circle one of the gum trees standing fifty metres from where my son and I were on the stairwell, and she took a long eye-level gaze at the trunk of the tree before walking over to it, turn to face the other way, and let her body fall back into the tree where, somehow, her body perfectly fit. I had not looked at the tree previously, but based on what I was seeing, it appears that in one side of the tree there was a gap, perhaps where the tree had rotted away and left an inclination, that cupped her body as if she was born out of that very tree. When I saw her enact this scene, I thought, that’s right, landscape as analogy, subject as object, she and the tree are two connected parts of a whole. She is the framework of subjectivity and the tree is the external world forged from its cast.

To talk about landscape and nature is to talk about oneself indirectly. Possibly it is the only manner in which to talk about oneself that is not socially repulsive. What I’m doing here, with this sort of writing and thinking about walking, is initiating the technology through which I escape from populated society. I enjoy living in the city, but I tend to believe that a city reaches its functional peak once it becomes empty of people. Well, so long as it leaves for my son and me to talk its silent quarters, where the city becomes an instrument, and the sunlight that forms triangles beneath our footfalls the bow with which it is played, resonating ghost songs that are, of course, love songs in their most pure form.

The TAFE, in its small, closed system intimacy, is a postage stamp compared with the city of Newcastle, which expands like a pop-up picture book from the paper’s edge on the north side of the TAFE. The dry storm-water drain that nestles here transitions with an abundance of water into Throsby Creek, a passage of industrial discharge that is, through local effort, becoming a little cleaner and more ecologically friendly each year. As a mark of this environmental progress, bull sharks have been spotted in the creek recently, the first in nearly a century since the last recorded shark attack was recorded there. A pathway that runs parallel to Throsby Creek takes you to where the Hunter River takes over, which, in our pop-up picture book, would be represented by a blue fold of paper structured not unlike a cathedral (in the same manner that Bach composed many of his late period organ pieces to structurally mirror the geometry of the churches they were to be performed in - the Hunter River at this juncture is steeped in a trajectory that could carry a bridal party down the aisle with the groom’s family on the ballast forged island where the coal ships unload, and the bride’s on the mainland).

There is a public art sculpture along here that uses a sturdy foam material, painted blue, with a white sphere in the middle, to resemble undulating ripples of water moving out from the sphere. My son calls this sculpture ‘the moon’, as in the moon has fallen in the water. It is perfect for climbing and rolling over. When our intentions are to head into Newcastle for the day, we often start at the moon (and, finish up at the beach, another analogy, another mirror, for what is the moon but a beach in space being cupped by the cosmic ocean, how the first astronauts wore the uniforms of deep-sea divers).

Sometimes we see other children of a similar age to my son who stop here with their parents to play, and, at the risk of sounding like a parent who can only see his children through the keyhole of his pasture, I observe how my son is often surprised by the antics of these other children. He doesn’t put a name to their behaviours in the same way I do – acts of deception, of street-wise trickery, of manipulation, of insider jokes that fuel a specific frame of intellectual and physical violence – but he does take noticeable stock of the difference in them compared to what he is used to, to me, in comparison with our own play. While my son and I build nests of trust out of familial servitude that fosters deep care between us, these other children build something different – a bridge away from home towards new learnings that I can’t replicate. Sure, that goes without saying, but they also bring a deprivation of innocence that my son still has in spades. This is because, other than growing up with his sister (ten years his elder), his experience with other children has not been plentiful at this point in his life. He sees them at playgrounds like this, of course, but he doesn’t attend daycare or preschool yet. Instead, he spends time with our family and, when I am not working, with me, exploring the rise and fall of mostly bare city quarters.

On past the moon is the marina and the fisherman’s co-operative. We stop behind the big exhaust fans on the side of the shed where heavily coated men drag crates of yellowfin and roughy, and we are taken with laughter by the blow of the fans as they push our hair seaward. Up the road is the new Interchange where the rail line meets the tram line, an anachronism depending on who you talk to; the whole city was once covered in tram lines connecting suburbs before they were taken up to make way for the future. Who could have seen that the future would direct the city to remove the inner-city tract of train rail and replace it with, guess what, another tram line, only this time it doesn’t connect the suburbs, it just goes up and down a spare kilometre of CBD. And then we have the trams themselves, in the beginning presented to the public wearing coats of crisp red and white paint draped across sleek mouldings, like a children’s toy given extra care during mass production, only to then some weeks on have another coat folded around them - plastic wrapped advertisements for the coal mining industry, for car insurance, for banks. As you peer through the slits of transparency in the advertisements to the interior of the tram cars and see the mostly vacant seats, it is apparent what the real value of these city assets are.

But those are the words of an adult cynic and do not reflect the feelings of my city companion. My son’s favourite tram is the one advertising a new kind of milk - ‘there it is, the milk tram’, he calls out as he sees it float from behind the boxing gymnasium into the clearway. The milk tram is an exciting piece of moving art that combines so many of my son’s most revered preferences (mostly his love of milk and public transport), and it brings about another favourite experience, watching the signal crossing lights shine into action and listening to their metronomic ding. Now that I realise what the milk tram means to my son, I temper my criticisms, not because my complaints are wrong, but because they’re a bit gross in the light of other perspectival shades. It reminds me that at times I too love the trams, ads and all, when from a distance I see their evening lights trace a line through the city like a vintage educational animation of electricity flowing up a circuit; and what about the lovers who have spent all night on the beach, slunk against each other in the otherwise empty carriage as morning sunlight smudges the glass terrarium that contains them and fosters their photosynthesis, twin piles of sand at their feet; or the autonomous humanoid care drones, en route for aged care lunchtime visitations, comfortably seated, vibing in ambient defragmentation, screen savers displaying health care practices, recommended sleep schedules; or for all that, how about the lack of trams, the inversion of their presence, on that one day when they were all locked away for compliance auditing and I walked the tracks, the white salted concrete tongue that rolls between hotels and bridges, drains and hospitals and art deco balustrades, theatres turned cinemas turned churches turned wasteland tundra, the last antique shop on the street, a custom electronics repair store that I took a broken MiniDisk player once, and a host of other sites and assorted memory prompts that I’d never previously had the opportunity to observe on foot from this vantage, a psychogeography born out of the temporary absence of trams, a non-place turned place for a little while.

The wedding district beyond the Interchange unfurls in snow-laced matrices across old multi-storey buildings, some with sheer glass facades that shimmer in laden dust light bearing rows of white dresses lined up on mannequins, looking from this angle like a giant game of Connect Four if all the disks were the same colour. Other buildings wear art deco concrete rendered caps painted salmon and tangerine, housing beneath them a couple of eateries peppered along the street that, ontologically speaking, only seem to vaguely exist at certain hours of the day and week. Around the corner is a pub not long in business, just opened before the pandemic. During lockdown they served supersized cocktails to people on the street, daiquiris in vases, ouzo in juice bottles, which someone commented was very European, although that seems a stretch.

A block up from here is a government building. They deal with where you can and can't dig, I believe. It is a structure made almost entirely of sand-toned pebblecrete, from the floors to the walls, and there are accessibility ramps that wrap around the building in all directions, a dream for my son to run and leap across, not unlike like a multi-storey hedge maze. We always end up here when no workers are around, probably on weekend mornings. My son likely thinks these buildings don't actually contain anything - no people, no objects - that they are shells like a fort made from cardboard, just walls, floor, and air, a space to be climbed over with no other function.

From here, we will often head to Civic Park, a stretch of parkland facing a doughnut-shaped building that was once our old Town Hall. The park sits at the feet of our city library and art gallery, the crucible of public frustration at one point after a row of fig trees that lined the street between the park and the library were set for removal by the city council. Environmental reports claimed weak root systems and risk of falling branches, while others gestured towards plans the council had to commercialise the space the figs currently occupied. After many months of protest and security guards patrolling the figs day and night to ensure no acts of urban terrorism were carried out, the figs were removed. A couple of years later, and I mention this with no political motive, a massive storm hit Newcastle and, ridiculously, I took to my car with a camera to photograph the damage being wrought across the city, finding telegraph poles being thrown around, rooftops ejected from buildings like smokestacks casting off their lids, and a host of fig trees, dozens of those that remained in the surrounding streets, plucked out of the ground and dropped onto cars and homes. All told, hundreds of trees across the city were prone to the same demise. It was such a peculiar phenomenon to observe as so many fell in the same way - footpaths folded back onto themselves in waves of grass, the gravity of the fallen tree having activated this fold, resembling one of those books for young readers where you peel back layers to see the internal workings of earth and machinery.

Back at Civic Park, there is a large fountain - a water feature really, structured around a sculptural piece of decimated stone. It has been reported that during World War Two a secret plan was developed that, in the event of invading troops ever making it to Newcastle and being in a position to take control of our smelting facilities, a sequence of explosions could be initiated from the top of town to flatten the city, rendering our factories, our entire infrastructure, impossible to be weaponised against the rest of the country. This fountain sculpture is, to my eyes, a vision of what might be left of Newcastle after this self-destruction was actioned, a broken symphony of splintered rock consumed by ocean waves. However, as with the milk trams, this is not what my little friend sees. He sees a motorised water toy set to motion by an engine room that sparks infinite curiosity. Some fifteen metres from the fountain, a narrow staircase of some dozen steps descend into the earth, becoming ever noisier, leading to a metal door we have never seen open. This must, we conclude, lead to the controls and the motor that keep the fountain running, although what sits behind the door is ultimately a mystery to both of us. A mystery we joyfully return to, week after week.

The next patch of town we wander into is where remembered dreams of my boyhood start to take form, where my steps from thirty years ago begin to overlap, ghost-like, with those of my son. A curve on King and Hunter Street brings about an old cinema that has been sitting empty for many years. You can look through the windows at movie posters from the last decade, a time capsule left unburied. I loved to go here as a lad, the dark carpet, the heavy burgundy curtains, the firm leather seats with the gold tacks holding everything in place. Occasionally I wonder what it would take to get inside and look around. But not now, not with my son. I remember my father telling me how many cinemas, ‘picture palaces’, used to exist around town. He and his mates would get on their bikes and, for some fractional coin currency no longer in circulation, would visit several across a single day, seeing a different cowboy movie at each. The original cinema buildings held Wurlitzer organs and orchestras, replaced over time by an empty field of space between the big screen and the first row of chairs where young children run around when they get bored, a non-space like those trams tracks without trams, an inversion of solid form, a lady cradling her body into the divot of a tree, a ghost song that disintegrates all memory of its melody upon waking up, realising that thirty years hence have brought you back here again.

Memories are never singular but rather always in the plural. There is no single memory, like an individual card pulled from a deck, but instead they exist as a multitude that fan out and lay across each other, like petals of a particularly transparent quality, the light of attentive recollection filtering through their combined hues. It is as if film negatives were laid one on top of the other to create an entirely new composite scene. Those individual scenes do not exist - only the assembled collage is real. The piling up of old memories produces new ones, forever changing how we see the past, like when we hear news about a neighbour that permanently alters our every perception of them. The past is always a spontaneous product of the present, constructed in an instant of reflection - not a chance use of the term, reflection - the surface of our mind bouncing light against the smudged layers of our plate glass memories, mirroring back to us a scene never before depicted that looks like something we’ve always known.

I remember the Angus Steak House a block up and across the road from the cinema. It housed a model train track pinned alongside the internal wall of the restaurant, running from the kitchen to the booths of lucky diners that sat alongside the rail line, a steam train puffing to-and-fro hauling carriages that gripped plates of warm garlic bread. I remember too another little train (ever the enthusiast, like my little man) on a track suspended around a tall iron pillar in a shopping arcade just a bit further up the street. The track ran through a mantle clock on one side of the rail and beneath a heavy bell suspended opposite. If my memory is correct, I believe the train used to sit within a tunnel cut inside the base of the mantle clock until the hands hit the hour mark. At this time, the train would leave its tunnel and drive out and strike the bell somehow (did the momentum of something attached to the train simply drive beneath the bell and hit it as it passed, or was it something more mechanical striking the bell, or did it actually hit the bell at all - the arcade was within a clear audible trajectory of the clock at Town Hall that strikes every hour, perhaps the bell was just ornamental and what we were actually hearing was the town hall bell).

As we walk this quarter, disintegrating with every step, multistory car parks replaced with apartment buildings, department stores with apartment buildings, old apartment buildings with etcetera (everywhere to live and nowhere to go), I experience a projected Proustian moment where I believe I can smell biscuits from the Cookieman section of David Jones, surely twenty years since it existed, not within my daughter’s thirteen-year lifespan or I would have taken her there to taste the jam drop shortbread, the biscuits with the yellow or green or red coloured lollies, the dotty cookies with chocolate buttons covered in hundreds and thousands that they used to call ‘jewels’. I used to go there with my parents, my mother, when I was, say, seven or eight, to select a biscuit when I was in the vicinity. The whole David Jones building was special. I remember Christmas season when my wife and I would go there for family gifts, the beautiful displays of jewellery, books, clothing, the only real store in the city for these sorts of purchases, thirty kilometres from the nearest suburban shopping centres that have come to dominate the era. I used to walk the car park alone on a weekend morning, winding up the on-ramps, overlooking the city, the harbour, the old abandoned Victoria Theatre.

And then the whole place shut down. One earthquake was all it took to dismantle the history of the CBD and send the future out to the satellite townships. David Jones sealed off its doors with sheets of plywood, and a process of memory evacuation was initialised to make room for non-memories, new spaces that don’t harbour the unseemly noise of dynamic remembrance. And yet, of course, some noise was left behind, not only within my own skull but within the artistic pursuits of local talents. One oil painter, a UK emigrant like so many of our best local creatives, gained access to the internal corridors of the David Jones building, the expansive tiled zones where whitegoods and children’s clothing were once stationed beneath mighty air conditioning ducts, and captured the scene in poppyseed and walnut, impasto slabs of dust, collapsed shelving, stacked chairs and cash registers left fallen in a corner pile, arched windows looking out to the sea - and look, when you press your face to the canvas, the windows show nothing: no world behind the painted portal, like a wall of memory that says no more data available, a visualisation of the voice on the old cassette tape that says ‘this is the end of Side A, turn the tape over’, to restart the memory from the beginning, or rather not the beginning but the other side, with a younger version of yourself.

I mentioned UK emigrants just now because it’s curious how many of the local artists and writers who frame much of the way I consider Newcastle came from the Isles - the author I referenced at the outset who wrote about following his dog into the gasworks as a subterfuge for his own explorations, the artist mentioned above who paints the remnant scenery of expired department stores, and another artist who created an illustrated catalogue of a hundred mailboxes from around these streets and who draws the same ephemera disjecta that pulls me in too, the bent wire fences of the velodrome, the anonymous walls of how many bricks that comprise the local telephone exchange, the foliage of fig trees cut through the middle by the council to make room for powerlines passing through, burrowing into the globe of leaves, turning full circles into caves, like the cave of the mantle clock that the little train would wait in for the hour mark (I’ve just remembered more on this, it was not the train that struck the bell, but instead there was the figure of a miner on a cart pulled behind the train that would hit the bell with a pick axe), like the metal offcuts found at the TAFE that form other mantle clocks, other mirrors of time.

More UK artists also come to mind - a photographer who would, until 2018, capture similar local scenes as just recounted and post them in a daily blog online. And a local historian I became friends with who moved here in her seventies and began researching the cultural foundations of the area, which she says helped her connect more deeply with her new home, to understand it more than many longtime residents, compensation for being the outsider. I wonder if being in a new, yet not wholly unfamiliar, environment sparks the creative urge to render a new home in a way that fosters a synthesised familiarity. Or, is it that travellers bring with them a capacity for enterprise, particularly artisan capacities, that gesture them into writing books and painting canvases about what else but the streets they wander every morning as they take stock of where they have ended up.

Travel was never something I yearned for, even as my close friends began making plans towards the end of high school, during university, to go to Europe or explore South-East Asia. I dug my heels in - what more could you want than what we have here, take a look around, the entire universe is stationed in Newcastle, like that Kafka quote about how you don't need to go to exotic locations to find the world, you just have to put yourself at your desk, still and alone, and the whole world will offer itself up to you. That being said, when I did start to travel as part of work opportunities, I relished the experience. On my first overseas trip for a conference in Bali, I couldn't quite believe I was standing on the ground of another country, across an ocean, an entirely different land mass. I still feel the uncanny sensation today, ten years on, recalling how I turned back on the Denpasar runway to see the Indian Ocean in a mist of afternoon cyan wonder. After being driven to the conference centre in the grove of some stunning tropical paradise, I immediately transgressed the trip's work health and safety governance by leaving the hotel boundaries. I remember pushing through a thicket of dense palms fronds on the edges of the venue and finding a cow in a wooden cage there, and then some paved steps that lead up to a cliffside restaurant, not open at the time and possibly closed for the season, where a little collared dog, speckled with black stripes on his caramel body, came up and followed me around. Wherever I travelled the following decade, I always seemed to stumble into the same solitary quarters I favour at home.

In New Zealand it was midnight in Christchurch, not long after the terrible earthquake that devastated the city, walking around the dozens of public artworks erected to commemorate the event and provide a space for community and memory to harmonise. I remember giant lounge chairs made from astroturf, a tower of multicoloured shipping containers, miniature golf courses with plastic funnels connecting holes between the remnants of fallen church domes, and those few remaining buildings wrapped in brown paper, like a bandage, on immense vacant plots of land. In China, it was arriving beneath a Christmas tree at the Peace Hotel in the Bund region in the middle of the night, and minutes later dreaming that I had missed the plane to China only to shock myself out of sleep and realise all was well, I was there. A walk through Old Shanghai after breakfast beneath immense coils of electrical cables suspended from the corners of stone block businesses, sharing the alleyways with little dogs wearing ballet shoes and tutus. Unable to find my way across the Huangpu River, I kept taking the sightseeing tunnel tour that puts you in a futuristic pod and shoots you from one side of the river to the other through a rainbow grid of lights, with an accompanying voiceover that describes that geological formation of the earth. Later, in Songjiang, I slept in a hospital for a week and walked the surrounding fields during the day. I visited a shopping centre one afternoon only to find that all the shops were an illusion - all the shopfronts were painted with pretend bakeries and bookstores. They were positioned beneath the shadow of infinitely replicated apartment buildings, fifty storeys high, which had, near the access gates at their base, little red signs bearing an illustration of Lenin on them with a red cross over the top, no Leninists allowed. I saw a little schoolhouse on one of my walks, a kilometre or two from a hotel wearing large sculpted letters reading GOLF on its front, that I tried without success to find later on a digital map. When I took a photo of the schoolhouse from a distance, it was a lovely scene positioned amongst an intersection of hill, field, river and empty superhighway, but the photo has since been lost.

When I visited Dubai, a place built for the touristic experience, I inadvertently found myself again in peopleless spaces. After learning that Dubai was not a walkable city, I asked a taxi to take me to where I thought was a spice souk was located, but the directions I gave took me to a barren waterfront area with flat tangerine-toned buildings that housed art galleries and museum attractions, all closed while I was there. I walked the area for two hours and found a rotating teacup ride, not in use, a wet floor sign in the shape of a banana, a statue of a robot made out of folded sheets of tin, and a river that seemed to display, across the water, a mirror image of the sights found here. Besides the taxi driver who dropped me off and another who picked me up, I didn’t see another person for the entire outing.

There were similar experiences in South Africa and Singapore – flying into major cities, but where are the people, how did I end up in the only empty quarter. This further stoked in me the joy of travelling somewhere new and, during the period before or after my work commitments, walking the urban and semi-rural trajectories that took me to areas in which I felt like I’d fallen off the map, as if I’ve blinked and awaken in a parallel version of the place in which you’re the only remaining soul. It is the same around Australia – notably, recently, Deloraine in Tasmania (the rail line beside the timber mill, the suspension bridge over the river, platypus diving between duck feet), Wee Waa (the red fields with kangaroo tracks where Daft Punk once performed, enormous trucks carrying hay bales the size of houses) and Inverell (ghost mist on Winter morning streets, candelabra street lights becoming alchemical, turning liquid vapour into frenetic gold sparks) in New South Wales, and just the other month to Glenelg in South Australia, where I travelled and left my home for the first time since my son was born, previously excused from doing so by flight bans during pandemic lockdown. I wrote a poem about processing being absent from him, of which the first couple of stanzas (in which, like a moth, I’m forever spellbound by light of any sort), go:

By the time I have arrived in the hotel room

and pushed through the gauze curtains

to see the sun, flat from this angle, sink within

minutes behind its own ribbon of gauze,

a distant cloudscape of embarrassed whisper,

I am some half day absent your little face.

You turned three on Saturday, likely the first

birthday that carried some resonance

to seperate it from all the other playful days.

But now I am here with you over there,

the first time since your birth that work travel

has become inescapable, try as I have.

To fight the grief when you are not pressed

to me tonight, not ‘morrow on bikes to

spin off into isometric concrete wonders,

I have committed to take witness re:

what is in your father's head (at thirty eight)

as I footfall this beachside destination,

as I see this sun fall into the ocean, I swear

it flickered like a light bulb on a bad

circuit, backlighting clouds when it touched

down into the ocean. Tomorrow the

newspapers will talk about an energy crisis

with not enough power on the grid,

not a coincidence in my eyes, just like the

skyline here painted in vibrant hues, it

is not saturated by chance, no - these reds,

akin your highly oxygenated blood

spilled through so many skinned knees,

they glow via Tongan volcanic dust.

Some of the road trips my wife and I took together, before our son was born and when our daughter was old enough to stay with family for a couple of nights, reveal a counterpoint between the kind of solitary spaces that urbanism brings in comparison with more pastoral locations. On one of our drives up north, we stopped at Bowling Alley Point and took a stroll up Peel River from the Chaffey Dam. It began to rain, and we had to refuge in a little weatherboard church on a hill (the roof of our car had a bad leak and gave no shelter). Inside, bathed in faint lemon rainlight that struggled to cast through a dusty window arched around a depiction of a fallen gum tree, we found a crossword puzzle in a newspaper beside the pulpit that we completed with a golf scorecard pencil. Back in the car, with towels on the seats, we ascended a mountain range, the name of which I cannot recall. When we reached the top, we pulled the car over to examine a kaleidoscope of tiny green butterflies that were, to my wife’s concern, hovering over the edge of the mountain (she didn’t feel they should risk being over such a high vertical drop, even though it seemed visually impossible to consider that their infinitely buoyant jostling would ever cease). I thought I could hear water lapping somewhere nearby, behind the car perhaps, and after we marched through some hundred metres of bushland away from the edge of the mountain, we found a tree-lined lake. It must have just been rainfall in an immense basin, like a volcanic crater, but it was stunning to stand and look at, thinking about how high up it was, very nearly amongst the clouds that filled it up.

That night, we reached our accommodation in a small regional village, although not so small that it didn’t have a cinema in a hall with around twenty white plastic picnic chairs set up in front of the screen. It sort of looked like a movie drive-in had a house built around it. The thing that really got our attention, though, was the retro arcade attached to the side of the cinema, through an aluminium security door with a torn flyscreen, into a sunroom with four or five machines from forty years ago. I can’t remember them all except that we played Golden Axe together for a good hour and then took turns on a Volley pinball machine (we were thrilled by the real mechanical action of the bumpers, the chain reactions that caused an immediate snap reflex the moment one of the hypotenuse pads were hit by a ball, like when a doctor uses a little hammer on the tendon in your knee to make your leg kick up).

So what is to be considered here about the aesthetic differences, or rather what I described earlier as a subphysicality, analogous to the shape of the inland empire of my subjectivity, that these different environments elicit - the riparian scrubland tundra of Bowling Alley Point (I always think of Salinger’s unpublished story ‘An Ocean Full of Bowling Balls’), the butterflies and the crater filled with rainwater, compared with the built environment, the cinema and the arcade, the rows of white plastic chairs. Is there a difference, or are they the same environments but on separated points on a singular timeline - one day, there is a pinball machine; the next, it is a gravel path that, when you kick a particular rock, the ground reflexively jolts the rock right back at you. Or perhaps both spaces fulfil different solitary needs. The built environment is a sign that someone was once there to build the place and had a reason for it to exist, even though it perhaps no longer serves a purpose. I think of that poem of Larkin’s where grass grows up through the floor of a church, deer now grazing there. Is it a post-human peace, an opportunity to enjoy the cultural remnants of humanity without people causing any further harm, aside from the witness there to see the last of it all, and if so, what does that say about me and my reasons for seeking these places out. It is easier to justify being alone with nature; it sounds so healthy, connecting with the biological heart of it all, the sunshine, the water, the peaceful pathways that let your mind disperse like the seeds of a dandelion. For me, the peak sensation of landscape is the fusion of these two spaces - the bomb shelter in the forest, the transmission towers amongst the wheat fields. And if you’ll excuse another poetic aside, thinking now about these scenes reminds me of a walk I took with my dog recently through just such an area, it goes:

There is always a hole in a fence,

eventually, that someone else has made.

Local hoodlums, is that still the word,

anticipated my palliate arrival with pliers,

somewhere to smoke or shoot up or shag,

is that still a word, but I’m thankful all

the same because there is nowhere else

in the city or the neighbourhood, is that

still a thing, to walk my dog today, for

all the good spots are taken and I don’t

trust him to be social with other dogs,

the only real trick I’ve ever taught him.

The fence hole is in an industrial

estate still being established, there is an

unused quarter, is that still a thing, where

I watch my dog run through yellow grass,

or not so much run as bound, is that the

word because it seems like he’s doing the

very opposite of being bound, because

giving a dog the opportunity to run free is

a handsome thing but also reminds you of

how this instinct is mostly restricted, but

not today my friend because just look at

where we have managed to find ourselves:

northward is nothing but sky,

I don’t mean straight above my head,

although that is also nothing, I mean to

the horizon, just some arm of a crane like

a twig from this distance, it pivots in an arc

like the gnomon of a sundial, pointing now

towards the old gun barrel radio station on

the hill that still distributes a signal, low

powered, someone messing around with

pirate frequencies, I know because I hear

directions being read by a man wearing

what sounds like a heavily pilled jumper.

Transmission towers daisy

chained by melancholy strings like

Elgar would have liked seeing bowed,

not heard necessarily, the visual would

have been enough as it is now, seeing

them become small as I back up towards

the fence line, who knew the ground

here would be so wet, is this what it has

come to, seeking out sunken fields in a

zone beyond the reason of townships,

through a hole in a fence (ok I admit it

was me who made the incision, is that

still a thing, admission, admission

into this area, but I jest), somewhere for

my dog to go unfettered, to walk without

neighbours, to see cranes and grass and

power pylons and rusted buildings on

the hill beneath Tuesday dry sunlight,

and while we need to turn back because

we have run out of solid ground, there

will be another day when we will return,

not phased by how messy this sludge

wander was, the nettles from the grass

pinned to us saying ‘take me with you’.

That line towards the start of the poem, 'I don't trust him to be social with other dogs, the only real trick I've ever taught him,' is nothing if not a confession as to the social exclusion these places offer me when my son and I explore the city together. And I'll say something else on this, something of a revelation that has just come to me as I walk with my son down Watt Street (its actual name, not a reference to the Beckett novel), passing by a quiet building I've always wondered about, an ex-services club that I can't be sure is still in operation. My first thought on seeing the building is that sense of query, wanting to know more about the place, what it's like inside, and the lives of those who go into such a seemingly, to my narrow field of observation, unoccupied space. And from there, I consider how I can learn more about it - can I wander out the back and look at the car park, and what if I put my face up to the window to peer through the curtains, or perhaps I can loiter in the lobby for a moment if the front door ever opens. What has never occurred to me, at least not in these last couple of years, is that I could ask about becoming a member of this club. Why not - I'm a decent, law-abiding citizen (well, peering through windows aside) who can surely afford an annual membership to a place like this. So why is my first instinct that I'm not allowed inside.

You could point to childhood factors, always a decent place to start. Some of my most cherished youthful memories are from when my parents took care of businesses after hours. As an only child, and one who didn’t contribute to the tasks my parents were involved in, I had time to myself for an evening to wander around wherever we were - for a period, it was a local council Information Centre with a car park I used to explore, climbing on concrete barricades and brick walls, walking down a tree-lined street beside a holiday caravan park that faced a twilight beach. Later, a public library, waiting for the vast interior to replace void with light as the power came on. I would walk up and down the stairwells, push into study rooms and administration areas, look through the shelves (I remember I was around nine when I found a book on Jungian psychology and the Australian landscape, of which I understood absolutely nothing, and yet something gleaned from the front and back covers stuck with me like a talisman for future discovery). There are many other locations as well that flit across my memory - an early childcare centre where I handled the peeling boxes of board games (why do I think of those buildings in Christchurch when I remember this); a garden in which I ran down a steep grass declivity into a greenhouse filled with hanging orchids; the garage of a local boxing historian that contained a poem about the horrors of the Vietnam War.

But is this really where my sensibility for tracts of urban solitude was developed, or is there a more visceral root. What about my stutter, significant as a child but less so now, what role did it play in all of this. Not necessarily as an isolating factor - it never stopped me from making friends - but what I believe it did do, and I think this is getting more to the heart of what I’m driving at here, is it taught me about different routes to achieve an outcome. On the one hand, there are the temporal strategies that stuttering teaches you, that you need to have around four or five different sentence options in your head at any one time that you can quickly divert to in order to finish a thought in case the original sentence begins to fail you. But the more important lesson for me is stuttering teaches you that while you might not succeed by going down the first, most obvious route, there are other possibilities, and perhaps those other possibilities are more statistically in your favour.

What do I mean by this - well, in class at school, you might not be able to provide an answer aloud to the teacher; but instead, you can ponder the solution for longer, keep it in your head to gestate, and then perhaps you write down the answer, not the answer you initially came up with but a more astute insight, developing a capacity for concentrated thought in lieu of being able to spontaneously get a response out of your mouth. I believe I intuited something from this position early on, the strategic options afforded to the outsider to find success via alternate paths. Instead of learning the piano, I learned the organ, a fast-track solution in some ways to standing out in your field (instead of being an average pianist amongst a sea of millions of other average pianists, you are an average organist in the sea of barely anybody else, and suddenly the word average doesn’t seem so fitting). Instead of teaching in a mainstream school, I taught in a special education environment. Was this just a numbers game, striking better odds at getting a job in a less populated field, or was there something more to it, an allegiance to others outside the majority. I’m drawing a bow here from being an only child with a stutter who explored after-hours council buildings to someone who developed an outsider mentality for success derived from anywhere the majority was not, through to where I am now, a father walking his son past an ex-services club and realising for the first time that he could become a member of that club if he just went in and asked.

I watch my son dance in a puddle on the footpath outside, and I get a flashback to my daughter doing the same thing ten years ago when she was the same age, in this exact spot, walking this same ground, and how we walked out the back of the club to the car park to pick seedpods from the ground. At thirteen, I wonder what I have taught her about being an insider and being an outsider, about being in the realm of people or being nestled in solitude by brutalist architecture, or being amongst teeming thousands cheering and syncing up in immense collective harmony compared with walking down a storm-water drain with your dog. In a twist on the old Groucho Marx joke, have I taught her that she can be a member of club that would accept someone like her. As I take my son’s hand and walk inside the ex-services club, wiping our feet at the door so we don’t muddy the lush red carpet within, I think about my plans for the weekend and how there might be somewhere out of town, not up the coast but down towards Sydney, that might provide a different landscape to calibrate some of these ideas. A bookstore in the Sydney CBD has a collection of books my daughter has been talking about lately. I think it’s time for a trip.

Chapter 2

The train journey from Newcastle to Sydney takes around two and a half hours, and we are lucky to have secured a Daysitter compartment on the regional train. With three seats it fits the two of us comfortably. My daughter sits against the window facing outside the train while I sit against the window facing the aisle where a rail guard walks back and forth. The restaurant car is open, and I buy my daughter a packet of chips and a bottle of water. Saying restaurant car feels anachronistic, or like I’m referencing an exotic travel feature from a journey far removed from here, and yet here it is, a restaurant car on a train between Newcastle and Sydney.

I’ve only been aware of this regional rail for the past two years, and this is only the second time I’ve used it. The first time was when I was looking for a way to travel home from Sydney just after the pandemic first hit Australia. Worried about being on one of the regular, crowded trains where I would be breathing directly into the faces of fellow travellers, I found out about the regional rail by chance (a sign on the platform perhaps, ticketed seats only, and I likely went from there). That was two years ago, and since then I’ve not returned to Sydney. I avoided going anywhere, certainly not to populated areas anyway. All of my work travel ceased. Each weekday I would wake, walk through the yard to my home office - a freestanding building that we constructed to replace an old, decrepit garage - and sit in a chair that, through dusty windows, drew in the morning sunlight. From there, I would work until the afternoon, at which time I would walk back through the yard to the house. A hermetic existence, to be sure, but one that I relished.

Tragic human toll aside, I could have readily maintained a pandemic lifestyle. Reducing people's movement throughout the neighbourhood made every weekday feel like Sunday. You could ride your bike down the middle of the road and not see a car for a good ten minutes. But that's me, approaching forty, finished with society. It was not necessarily the same experience for my daughter, eleven when the pandemic began and thirteen when routines from the before-times returned. That's part of what is fuelling this trip to Sydney, to get out of the house, out of the neighbourhood, to check out big bookstores and be amongst the populace again. She wants Sailor Moon manga, and for that, you have to head to the big smoke.

Through Wondabyne and past the only railway station in Australia that is inaccessible by road, we look across Mullet Creek towards the mountain opposite, about which my daughter informs me that etched into a portion of its rocks are Egyptian-themed glyphs, assumed now to be the result of a practical joker from the 1920s imitating the cultural excitement about the boy king, Tutankhamun, at the time his tomb was found. My daughter has recently been up there on a walk of Darkinjung country, eager to connect with this part of her cultural heritage and feel part of a more significant historic trajectory than can otherwise be found within the boundaries of our yard. She sits, eats her chips, and looks across the water before asking if we can play some music, softly, in our Daysitter compartment.

The track she plays hears a synthetic voice, perhaps two different voices, sing a skittering melody over bubblegum pop beats. She says the style of music is called Vocaloid, named after a piece of software that imitates singing. You type in lyrics, choose the notes, adjust the parameters, hit play and then you have your soprano. She says there are different characters for the voices you can choose from, Japanese anime-styled men and women created to give a face to each voice, each line of code. I remember seeing these now, watching a video from ten years ago of a virtual performance given on stage at a concert in Tokyo, a hologram of a digital girl projected onto a stage in front of thousands of young people waving neon rods in sync with the tunes. That’s the thing, my daughter says, these songs are old now, Vocaloid peaked ten years ago. Virtual concerts of hologram pop stars using their artificial vocal cords to sing impossible songs are so yesterday. But she has only just discovered them, the equivalent to me hearing Don’t Dream It’s Over by Crowded House in 1996 when I was thirteen, a decade after its release. She is nostalgic, at thirteen, for the most futuristic music imaginable, because its wave has already crested.

It's fitting that I picked a 1980s song to reference just now because the tune my daughter is playing abruptly makes me feel nostalgic for my childhood during that period, or perhaps just a little bit later, the first years of the 90s. Something about the interplay of the melody with these twinkling synthesisers, the way they sparkle in major chromatic runs like little fireworks released every four beats. It brings to my mind a series of overlapping musical memories.

The first is the background music to a stage of the game Sonic the Hedgehog. Starlight Zone, the stage was called. I can see it now - black backdrop with blinking stars forged out of white pixels fading in and out of the sky, floating khaki platforms for the blue hedgehog to spin across, and the music, four repetitious notes that first step up two tones and then bounce up an octave and trip back down a semi-tone, followed by a flurry of jazzy syncopated cocktail chords, nearly Bossanova infused (or am I just thinking that because now I'm thinking of space and I'm associating it with supernova).

My second memory that connects here is the Starlight Room on the second floor of a local bistro and leagues club in our area. These days I see it as just another conference room, but when I was around six or seven I walked up around the turn of its red velvet staircase, possibly not even getting beyond the stairs because I was only allowed to walk up a little of the way by myself while my parents were talking with grandparents on the landing below, and I witnessed, hewn within the ceiling, a stunning galaxy of little pulsating lights that gave the Starlight Room its name. There was muzak playing that I cannot precisely recall other than to say I would not be surprised if it was the exact backing track for what we're listening to now.

The third connecting musical memory is an advertisement for an album by the group Simply Red that, for a season of my childhood, seemed to air between every cartoon I watched. One particular song, Stars, I can remember being highlighted on the television advert, and while there seems little musical connection between that song and this Vocaloid tune, there is something about the melody that resonates here, and it feels as though the muzak I cannot recall from the stairwell of the Starlight Room would naturally interpolate here as well.

My final musical memory illuminated by this tune is another advertisement, or more accurately, a trailer for a film that must have been on a video cassette that I watched around this same period, for The Jetsons Movie, based on the 1960s cartoon about a family who lives in the future with flying cars and a robot housemaid. There is a moment in the trailer that I recall where a song is announced, the voice-over says something like 'Featuring a new original song by' some group, and then this electro-clash pop rock tune comes on while the daughter of the Jetson family, Judy, dances around a sparkly cave with a blue alien teenager wielding an electric guitar. I think there are also little fluffy alien animals, like hamsters and hedgehogs, who gaze out from the cave depths, watching the dance performance which elevates Judy and the blue teenager up through the area without regard for the conventions of gravity.

All of these associations spontaneously come to me after the first verse of the Vocaloid song, inspired not by the lyrics, which I cannot decipher, but from the tone of the synthesisers that twinkle and sparkle; they have a sharp angle to them like a triangle wave, partnered with the jolting shape of the melodies they're forming. When I ask my daughter what this song is called, she says Gemini. The star constellation for the cosmic twins, which of course, makes perfect sense - an interstellar analogy. On one side is this music we're listening to; on the other, there are musical memories that conceptually mirror the song's reflexive sensory associations, forged at this moment as a single glittering musical experience that, like all analogies, see two become one.

After we listen to Gemini, my daughter plays the song again, but this time covered, sung by a human. They have a good voice, hit all the correct pitches and sing the fast bits with precision, but it sounds different and not in the obvious way you'd expect. Discourse on the digital production of art is often with deference to the superiority of the human spirit in the act of creation; even as artificially intelligent art algorithms win awards over their human competitors, there is the persistent background reminder that it was a human who wrote the code that made the robots draw and speak, so at heart, all art is still a human creation. And that's fine, but it isn't the most interesting part about listening to this human voice and comparing it with the software we just heard.

It strikes me that, within this Gemini song, the angle of the melodies the human is singing makes the music sound more artificial than when the software was performing it. Listening to the way the notes jump half octaves up and down, trilling a quaver before running down a flurry of descending grace notes - when they fly out of the mouth of the robot they sound so natural, like a songbird on a branch greeting the morning star, and yet from the tongue of this human the same notes sound robotic. I wonder what the term for this phenomenon is – we call it the 'uncanny valley' when a robot tries to act like a human but doesn't entirely sell the performance, but what about the opposite, when the robot sings notes that are written for it and sound more like a product of nature than when the human performs the same task. And that's the key, that the music was written for the robot, that's what creates the effect, which leads me to wonder what other parts of art and society and language and democracy and thought will be written for robots to perform in a state of natural grace in ways that humans will come up short against. When I say 'will be written', I should be saying 'will continue to be written'. At work when I make a mistake, or someone else does, I say, 'well, it's just a sign that the robots haven't taken over yet; there is still room for human error, and for that we should be happy', but really if I took a good look at the shelf life of that sentiment, I would know it has already expired.

We arrive within the depths of Town Hall Station, intricately layered within century-old corridors lit with gold glass lanterns the shape of pineapples, sliding scissor gates on elevators a hundred metres beneath ground level, beneath the Queen Victoria Building that contains its own knotty layers of spiral stairs that mostly lead to nowhere but sometimes lead to old clocks and bells, and at Christmas a view from all angles of an immense tree that ascends from above the station concourse through to a star suspended from the glass dome at the building’s apogee four stories above. Christmas is mostly when we come here, a couple of days each year or two in the city over the Summer, a tradition we commenced when my daughter was five - perhaps a swim at the city pool, a walk through The Rocks, and a visit here to the Queen Victoria Building, especially a little toy shop on the top floor that displays beautiful heritage dolls and carriages in its windows. My daughter would walk past these, though, and head straight for the fantastical beasts that occupied a medieval castle near the cash register, where she would sit and play and pick out a Cerberus or an armoured dragon to take on the train ride home. And, one year, we covertly took the castle home, too, ready to be opened on Christmas day.

Out on the street, we spot a busker dressed in yellow pyjamas with a green leaf atop his head, the costume of a video game character my daughter enjoys, a half-flower half-animal creation called a Pikmin. He’s playing a rapid breakbeat on empty pasta sauce buckets, and he spins his drumsticks and shows his teeth in a massive smile whenever someone drops some coins on his mat and takes his photo. This is already a thrilling trip into the city - where else would you spot a happy Pikmin playing drums on the street. I point to glass windows two stories above his head, our bookstore destination.

The store resides in what is called The Galeries, a further collection of winding corridors (a persistent theme of this trip, corridors that lead to more corridors, until you’re not sure if you’ve crossed beneath or above a street in the meantime, walking in one entrance and suddenly finding yourself on another side of the city) that used to house the Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts, the oldest continuous lending library in Australia. I used to see various Mechanics Institutes on trips across the state, often housed in beautiful sandstone buildings kept in a heritage state, such as the one a suburb over from our home, the Lambton Mechanics Institute, and wondered for years what they had to do with mechanics before I learned they were established as sites of adult learning, providing an opportunity for literacy and access to newspapers and journals, and lending libraries like the one established here in The Galeries.